Clinic for Gynecology with a Center for Oncological Surgery

Those affected and their relatives often experience the diagnosis of ovarian cancer as a deep turning point in life: it is not uncommon for fear, stress and other psychological stress to be the result. There are various options for support and help — both in the direct environment and from various experts. With our contribution to the treatment of ovarian cancer, we would like to show cancer patients, their families and friends ways to better understand and deal with the disease In the following you can read how a therapy typically proceeds from diagnosis.

1. Consultation hour

Do some research before and after your visits to get answers to all your questions.

First of all, your doctor will ask you what will lead you to him or her. He or she will want to know which examinations have already been done and whether you have written documents for them, because these can be very helpful. Please bring all the documents you have about your state of health with you. You may also be asked about your complaints. Knowing about the symptoms does not necessarily help to clarify whether it is ovarian cancer.

Then a gynecological speculum and palpation examination of the vagina (vaginal), the abdomen (abdominal) and partly also the rectum (rectal) take place, as you already know from the gynecological practice. This examination is supplemented by a vaginal (and possibly abdominal) ultrasound and a determination of the tumor markers (including CA 125, CA 19–9, HE4). The tumor markers only serve as indicative findings and are used to monitor the progress, e.g. after an operation. They are not always suitable as a specific indicator of ovarian cancer, since inflammatory diseases, for example, can also be associated with an increase in the tumor marker.

Your doctor may also order a computed tomography (CT) scan. This procedure is used to assess the spread of the tumor and enables good preparation for the operation, which is almost always necessary.

The actual confirmation of the diagnosis is only possible by taking a tissue sample. If ovarian carcinoma is suspected, this is obtained during an operation; if ovarian carcinoma is confirmed, another major operation usually has to be performed. If ovarian cancer is very likely, this tissue sample can also be taken right at the beginning of the major operation, which will only be proceeded after the final diagnosis by the pathologist. After knowing all of the examination results, your doctor will discuss and plan this operation with you.

2. Diagnostics

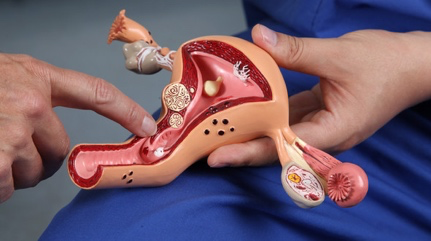

The most important examination if it is suspected that ovarian cancer could be the case is the gynecological examination as you know it from practice, which is then carried out by an experienced ovarian cancer expert. In addition, the anus is then usually examined from the rectum. This is followed by an ultrasound examination of the vagina and abdomen.

The next step is usually a blood test to determine the tumor marker for ovarian cancer in the blood. The result can help to make the diagnosis but is not always meaningful.

Imaging with computed tomography (CT) may be necessary, but by no means always. In the case of very small, unclear herds, position emission tomography (PET-CT) may also be used, but this is very rarely only necessary.

For this purpose, you will receive an appointment at the Charité’s radiology department via our patient management; the results of the examination can usually be viewed by the doctors in our department after 5 days.

Final certainty can only be obtained through a fine tissue examination. For this, a tissue sample must be obtained from the abdomen in an operation and sent to the pathologist. You look at the tissue under the microscope and can tell whether it is a benign or malignant growth.

3. Operation

The standard treatment for ovarian cancer is almost always surgery first. This should be done within 2–3 weeks of the diagnosis. The aim of the operation is to confirm the diagnosis, determine the extent of the tumor and completely remove (visible) tumor tissue. If this is not completely possible, an attempt is made to remove as much tumor tissue as possible, because the smaller the remaining tumor, the better the prognosis (long-term survival).

The operation has three objectives:

- Confirmation and scope of the diagnosis (through histological analysis of tumor tissue)

- Determination of tumor spread

- Maximum tumor reduction or removal

The operation is carried out via a longitudinal abdominal incision (longitudinal laparotomy) from the pubic bone to the navel and, depending on the extent of the operation, even to the lower edge of the sternum. Surgery for ovarian cancer usually takes 3–6 hours. Among other things, due to the confirmation of the diagnosis using a tissue sample. The pathologist examines this directly (quick section) and communicates the result to the surgeon over the phone, who then decides on the further extent of the operation. The surgery usually includes:

- Complete palpation of the abdominal cavity with removal of parts of the peritoneum if necessary

- Removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), fallopian tubes, and ovaries (adnexectomy)

- Removal of the large network, a lymph organ hanging from the intestine (omentectomy) and the enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy) in the small pelvis and along the large vessels (main artery, large inferior vena cava)

- If necessary, appendectomy (appendectomy), if it is a mucus-producing tumor

In addition, if necessary, all other areas affected by the tumor are removed. Organs or parts of organs may also have to be removed. For example, the spleen, part of the liver, part of the diaphragm or, more often, part of the intestine. If part of the intestine has to be removed, the affected part is usually cut out and the healthy ends sewn back together directly. But sometimes it can also be necessary to create an artificial anus, usually when the healthy bowel is too short to create a direct connection or other sutures first need rest from the bowel movement. In this case, the artificial anus can be relocated back after a healing phase.

After the operation you will first spend a few hours in the recovery room, where you will be asked whether you are in pain and will be given additional pain medication immediately if necessary. As a rule, the anesthetists also put a peridual catheter (PDA) before the operation, as is also the case with childbirth, which makes it possible for you to experience as little pain as possible. You will likely be transferred from the recovery room to an intensive care unit for a day or two. After mostly 2 days, you will then continue to be cared for in a normal hospital ward until you can usually be discharged home after 10 days.

While you are recovering from the operation and with the help of the physiotherapists and nurses on the ward, get back on your feet as quickly as possible and, for example, get your own tea, the results of the operation and the tissue examination are discussed in a tumor conference . In the tumor conference, experts from oncology, gynecology, radiology and radiation therapy meet and decide together which further treatment steps are necessary and recommended to you.

After the operation — checklist questions to ask my doctor:

- Do I have a high-grade or a low-grade carcinoma?

- What stage is my illness at?

- What other treatments do you recommend?

- What treatment options are available for me and why?

- What are their advantages or disadvantages?

- How much time do I have to make a decision? Would you recommend that I get a second opinion?

- When is my next appointment?

4. Genetic testing

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women. Around every 10th woman will develop it in the course of her life. The majority of these diseases occur sporadically, only about 5 to a maximum of 10% of the diseases can be traced back to individual genetic changes and thus occur more frequently in families. These genetic changes can also be associated with an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Testing for this genetic change (BRCA 1 or 2 mutation) can also be decisive for treatment planning in ovarian cancer, as there are drugs that can only be used if there is a genetic change.

The suspicion of a hereditary cause of breast cancer cannot be raised on the basis of an individual disease, but is made taking family history into account. If you have one of the following criteria, there could be a genetic predisposition. In this case, please speak to your doctor. Genetic counseling should be offered to all women with ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer.

Families with:

- at least three women are or have had breast cancer, regardless of age.

- at least two women have or were diagnosed with breast cancer, one of them before the age of 51.

- at least one woman is or has had breast cancer and one woman has ovarian cancer.

- at least two women have or were diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

- at least a woman has or has had breast or ovarian cancer.

- at least a woman has or was diagnosed with breast cancer when she was 35 years or younger.

- at least a woman has or has had bilateral breast cancer, the first time when she was 50 years old or younger.

- A man has had breast cancer and a woman has breast or ovarian cancer, regardless of age.

- A woman has or has had triple negative breast cancer.

- A woman has or was diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

Source: Center for Familial Breast and Ovarian Cancer Consultation Hours

Genetic testing can be carried out with a blood sample and also with a tumor sample. You can read about the BRCA mutation / genetic breast and / or ovarian cancer on this page in a few weeks.

5. Chemotherapy

Almost without exception, chemotherapy follows the operation to combat malignant cells that have remained in the body (adjuvant therapy). In addition, chemotherapy can be used before a planned major operation to reduce the size of the tumor (neoadjuvant) or, in the case of incurable tumor diseases, to relieve symptoms (palliative).

The first chemotherapy should be given within 4 to 6 weeks from the day of surgery.

Chemotherapeutic drugs (cytostatics) are able to kill tumor cells or at least inhibit their growth. They are usually given intravenously (into a vein) and are distributed throughout the body and also act throughout the body. Chemotherapeutic agents (cytostatic agents) attack cells that are growing or dividing particularly quickly. A property that is particularly true of cancer cells. However, healthy body cells are also affected, which explains the side effects of chemotherapy. Fortunately, unlike cancer cells, our healthy body cells have repair mechanisms to repair the damage caused by cytostatic drugs.

However, as a side effect of this highly effective therapy, all of your body hair will fall out. But after the end of the therapy they grow back immediately. Even if most patients get through the therapy with almost no other side effects thanks to supportive medication, nausea and vomiting and a weakened immune defense and blood clotting can occur. The fingertips and palms of the hands may also tingle due to the effect on the fine nerve cells there; this side effect, as well as unsightly discoloration of the fingernails, usually regress after the therapy. Stay in touch with your doctor and nurses about your side effects. They can certainly offer you further supportive measures before it becomes necessary to reduce or discontinue the therapy.

Chemotherapy for ovarian cancer consists of 2 drugs, namely carboplatin and paclitaxel. The drugs are given 6 times with a minimum interval of 3 weeks. A therapy session lasts about 4–6 hours and this is what doctors call chemotherapy, the period of 3 weeks after chemotherapy is called a cycle. In total, chemotherapy takes place in 6 cycles.

Before the chemotherapy, your doctor will inform you and you must also sign that you consent to the treatment. You can also ask your own questions during this conversation.

Before each medication, a blood test is necessary to determine whether your kidneys and immune system are fit enough for the therapy. This blood sample can also be taken in a practice near you, in which case the results of the blood test must be faxed to the chemo outpatient department 2 days before the chemotherapy appointment. Thanks a lot for this. We also need information about your height and current weight, as the dose of therapy is adapted to your body.

Chemotherapy is best given through a port. A port is a small metal chamber that is placed under the skin on the base of the breast and is connected to the blood system. This requires a very small operation, which is usually carried out by the doctors in radiology under local anesthesia.

6. Antibody therapy / conservation therapy

In addition to chemotherapy, the antibody bevacizumab (Avastin) is used for treatment in addition to chemotherapy in ovarian cancer, which also affects the upper part of the abdomen. This antibody therapy inhibits cancer growth by suppressing the formation of new blood vessels. As a result, the cancer, which needs a lot of blood to grow, is no longer adequately supplied with oxygen and nutrients.

This therapy is usually given from the 2nd cycle of chemotherapy along with chemotherapy. After chemotherapy, antibody therapy should be continued every 3 weeks for a total of 15 months. The hair will grow back again during this time and the other possible side effects of chemotherapy will already subside.

Conservational therapy:

The PARP inhibitors are also slowly finding their way into therapy, even with the first occurrence of ovarian cancer and are not only used for relapses, as they have been for several years PARP inhibitors inhibit the DNA repair mechanisms of tumors.

You probably know that cell division creates two identical copies of a cell, each with a complete set of genes (DNA). During this doubling process, mistakes can naturally arise spontaneously in the double-stranded DNA, e.g. in which pieces of the genetic information of a single strand break off. These errors in the copying process are also one of the reasons why cancer can develop in the first place. Normally, these errors are corrected by genes (for example BRCA1 / 2) that are responsible for the formation of repair enzymes (such as poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP)). However, if these genes are modified in such a way that the enzymes cannot produce them, the repair process cannot take place. This would be fatal for healthy cells, but not so bad for cancer cells, since the DNA damage can ultimately bring tumor growth to a standstill.

So researchers have taken these processes in the cellular microcosm as a model and developed drugs that specifically inhibit the cancer’s own repair mechanisms: the so-called PARP inhibitors. These enzyme inhibitors bind to the complex of DNA and repair enzyme of the tumor, so that, among other things, the entire double strand breaks. What is possible with normal body cells is not possible with cancer cells: namely, repairing double-strand breaks. Instead, the cancer tries to find alternative ways to repair DNA in order to survive. This also leads to the destabilization of the DNA until the cell is practically driven into “suicide” and tumor growth comes to a complete standstill.

These relatively new PARP inhibitors work hand in hand with chemotherapeutic agents that specifically cause DNA damage in the tumor. If the treating physicians have determined that the tumor has changes (mutations) in specific tumor-suppressing genes, the inhibitor can be used in combination with chemotherapy or as maintenance therapy after the chemotherapy cycles. This is particularly important when there is a high probability that the tumor will return despite standard therapy, e.g. if it is discovered late. The therapy currently seems to be actually effective in various cancers, such as breast, fallopian tube, peritoneum and especially ovarian cancer. Studies show that PARP inhibitors in such cancers increase the time it takes for the tumor to recur from an average of one to around four years.

Side effects

Unfortunately, side effects cannot always be avoided with this therapy either. Tiredness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, worsening liver and kidney values, anemia and a lack of blood platelets can affect your well-being to a greater or lesser extent. Under certain circumstances, the side effects can be so severe that the therapy has to be interrupted or reduced. If such a therapy is carried out on you, your attending doctor will certainly always remain in dialogue with you and choose the most promising option for you. If you have any questions about this, don’t hesitate to ask.

The health insurance company will assume the costs

Not all health insurances have yet to cover the costs of treatment with PARP inhibitors when ovarian cancer first occurs. However, you can ask your doctor to apply for reimbursement if the treatment is suitable for you. Alternatively, your doctor may be able to find a clinical study in which you can benefit from free treatment with the inhibitor and intensive medical supervision at the same time.

7. Follow-up care

After cancer treatment, we recommend that you take part in regular medical follow-up care. Here, not only are examinations carried out to detect a recurrence of the cancer at an early stage, but also

You should also be supported and accompanied in your recovery. Follow-up care roughly covers the period in which the patient is still dealing with the consequences of the disease and its treatment.

Examination intervals:

Since the risk of a relapse (recurrence of the disease) in ovarian cancer is highest within the first 3 years after the operation, close follow-up examinations are carried out during this time:

- Up to 3 years after surgery: Follow-up examinations every 10–12 weeks

- From the 3rd year after the operation: Follow-up examinations every 6 months

- From the 5th year after the operation: Follow-up examinations every 6–12 months

These are general recommendations that serve as a guide. Your doctors will work with you to create an individual aftercare plan based on your individual situation.

Examination:

The follow-up examination for ovarian cancer consists of a conversation in which you are asked about typical symptoms that could be a sign of a recurrence of the disease, as well as a gynecological examination with rectal palpation and a gynecological ultrasound of the vagina and an ultrasound of the abdomen.

In addition, the tumor marker Ca125 is determined, the course of which, not the individual value, can also be meaningful.

A CT examination is only necessary if the examination revealed unclear abnormalities. After the examination, there is also the opportunity to speak to your doctor about topics that concern you or about which you have questions. The best thing to do is to prepare and make a few notes beforehand about what you want to talk about.

Possible topics for your follow-up consultation:

- Nutrition

- Sexuality

- Prevention

- Rehabilitation

- Dealing with my family

- Additional psycho-oncological support

- Creative therapies

- Healthy living

- Social problems

- Genetic predisposition